The Center for Preventive Action has compiled an accessible overview of the Afghan peace negotiations, including the U.S.-Taliban agreement, the U.S.-Afghan government joint declaration, and the ongoing intra-Afghan process.

Last updated September 11, 2020 8:00 am (EST)

Facebook X LinkedIn Email

A peaceful settlement to the ongoing war in Afghanistan may now be within reach. In February 2020, the United States reached an agreement with the Taliban, and also signed a declaration with the government of Afghanistan to encourage the start to an intra-Afghan peace process. Many challenges still stand in the way of a successful outcome to these negotiations and, with it, an end to the United States' longest war. The Center for Preventive Action (CPA) has compiled this resource page on the prospects for peace in Afghanistan, including background on the recently signed agreements, the main challenges and concerns surrounding the implementation of the agreements, and the roles of powerful regional actors and their influence.

After lengthy negotiations, the U.S.-Taliban agreement and U.S.-Afghan government joint declaration were signed in February 2020. These agreements have been seen as necessary and important first steps to intra-Afghan negotiations—and therefore to achieving peace in Afghanistan—but they do not guarantee that intra-Afghan negotiations will be successful.

The U.S.-Taliban “Agreement for Bringing Peace to Afghanistan” [PDF] was signed by U.S. Special Representative for Afghanistan Reconciliation Zalmay Khalilzad and the Taliban’s Political Deputy and Head of the Political Office Mullah Abdul Ghani Baradar on February 29, 2020, in Doha, Qatar.

The agreement follows more than eighteen months—and nine rounds—of peace talks, involving Khalilzad, representatives from the Taliban, delegations from the Afghan government, and numerous other special representatives or envoys from neighboring or regional countries and international organizations. The signing of the deal was preceded by a seven-day reduction in violence agreement that was seen as a test of the Taliban’s ability to control its forces.

The agreement outlines four goals, with the last two dependent on the status of the first two:

More From Our Experts1. Armed groups will be prevented (by the Taliban and Afghan security forces) from using Afghanistan as a base for acts against the United States and its allies.

The Taliban agreed that it will not threaten the United States or its allies, and that it will prevent armed groups and others in Afghanistan from doing the same. The Taliban also committed to sending “a clear message” that it will not cooperate with those intent on such activities.

2. Foreign forces will withdraw from Afghanistan, including U.S. troops and contractors and coalition forces.

The United States committed to withdrawing all of its military forces—as well as those of allies, partners, and civilian security personnel—within fourteen months of signing the agreement, pending the Taliban’s demonstration of commitment to the agreement. Presumably as a show of good faith, the United States also committed to drawing down its troops to 8,600, and withdrawing from 5 military bases within the first 135 days.

3. Intra-Afghan negotiations were notionally scheduled to begin on March 10, 2020.

The start of negotiations has been dependent on the ability of the Taliban and the Afghan government to release one thousand prisoners and five thousand prisoners respectively, with the ultimate goal of releasing all political prisoners three months after talks begin. Once negotiations have started, the United States has committed to reviewing its sanctions against the Taliban, and working with the UN Security Council and Afghan government to remove their Taliban-related sanctions as well.

Preventive Action Update4. The agenda for intra-Afghan negotiations will include discussion of how to implement a permanent and comprehensive cease-fire, and a political roadmap for the future of Afghanistan.

The United States and the Taliban agreed that they seek a “post-settlement Afghan Islamic government.” Pending successful negotiations and an agreed-upon settlement, the United States has agreed to seek economic cooperation from allies and UN member states for Afghan reconstruction efforts, and has pledged no further domestic interference in Afghanistan.

In addition to the formal, signed agreement [PDF] between the United States and the Taliban, it has been reported by the New York Times and others that the agreement also includes classified annexes. In February 2020, members of Congress wrote a letter to Secretary of State Mike Pompeo and Secretary of Defense Mark T. Esper outlining their concerns over these annexes, specifically over suggestions that the United States would begin sharing intelligence with the Taliban. U.S. Defense and State Department officials have since indicated that there are classified elements of the agreement that likely reference conditions for the United States’ troop drawdown.

The same day that U.S. and Taliban negotiators signed the U.S.-Taliban agreement in Doha, Secretary of Defense Esper, North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) Secretary Jens Stoltenberg, and Afghan President Ashraf Ghani signed a joint declaration [PDF] in Kabul, Afghanistan. Similar to the U.S.-Taliban agreement, the joint declaration identifies four goals for achieving peace in Afghanistan and regional stability, with the last two goals dependent on the status of the first two:

1. Prevent terrorist groups from using Afghanistan as a base for attacks against the United States and its allies.

Unlike the U.S.-Taliban agreement, the joint declaration specifically references terrorist groups al-Qaeda and the self-proclaimed Islamic State in Khorasan, rather than “armed groups.” The United States and NATO committed to continue training Afghan security forces (per existing security agreements [PDF]) and conducting counterterrorism operations, while the Afghan government committed to preventing these terrorist groups from using Afghanistan as a base and continuing to conduct counterterrorism and counter-narcotic operations.

2. Establish a timeline for withdrawing all foreign troops from Afghanistan.

Similar to the U.S.-Taliban agreement, the United States agreed to reduce its forces to 8,600 within the first 135 days of signing the agreement, and to withdraw all of its troops within 14 months, pending the Taliban’s fulfillment of its agreement with the United States. The United States also agreed to continue seeking funds for the training, equipping, and advising of Afghan security forces.

3. Agree on a political settlement for the future of Afghanistan, following intra-Afghan negotiations.

The Afghan government agreed to join intra-Afghan negotiations, provided the Taliban meets the conditions outlined in the U.S.-Taliban agreement, and committed to discussions about prisoner releases. With the United States, the Afghan government also agreed to begin reviewing its sanctions against the Taliban after intra-Afghan negotiations begin. The United States, for its part, confirmed its commitment to seeking UN Security Council approval for future agreements, working with the Afghan government on reconstruction efforts, and refraining from interference in Afghanistan’s domestic affairs.

4. Establish a permanent and comprehensive cease-fire.

Both the U.S.-Taliban agreement and joint declaration resolve to establish a permanent cease-fire in Afghanistan as a precondition for achieving a political settlement.

In addition to these goals, the United States, NATO, and the Afghan government have agreed that they will work together to ensure that Afghan institutions continue to promote social and economic advances, protect the rights of Afghan citizens, and support democratic norms.

For more on the initial agreements, explore CFR’s Backgrounder, “U.S.-Taliban Peace Deal: What to Know” and view CFR’s timeline, “The U.S. War in Afghanistan.”

Under the U.S.-Taliban agreement, talks between the Afghan government and the Taliban were supposed to begin on March 10, 2020, following an initial prisoner swap. However, the Afghan government had not been consulted on or agreed to the exchange, in which the Afghan government would commit to releasing five thousand Taliban prisoners and the Taliban would release one thousand Afghan security forces prisoners. As a result, the prisoner exchange immediately became a contentious issue and talks were delayed.

Despite initial disagreements over the prisoner exchange as well as ongoing Taliban attacks on Afghan government forces, however, the Taliban and Afghan government began to discuss a timeline and location for intra-Afghan talks. In March 2020, the Afghan government named a twenty-one member negotiation team for the talks, comprised of “politicians, former officials and representatives of civil society,” including five women. The Afghan government also eventually agreed to an initial release of 1,500 prisoners and to negotiate on the release of additional prisoners as part of an ongoing process.

Under the power-sharing agreement reached between Ashraf Ghani and Abdullah Abdullah in May 2020, Abdullah was named chairman of the High Council for National Reconciliation, a group that will have final say on whether or not to sign any agreement negotiated with the Taliban. In June 2020, the Taliban and Afghan government confirmed that they will meet in Doha for the first round of talks; the Afghan government, however, was careful in its framing of the prospective meeting, emphasizing that no agreement or consensus had been reached on a location for direct negotiations. In late July, the Afghan government and Taliban observed a three-day cease-fire in observance of Eid al-Adha and, finally, in September 2020, representatives of the Afghan government and Taliban held a ceremony to mark the official start to peace talks in Doha.

U.S. Special Representative for Afghanistan Reconciliation Zalmay Khalilzad and U.S. Army General and Commander of NATO’s Resolute Support Mission Scott Miller attend the inauguration of Afghan President Ashraf Ghani in Kabul, Afghanistan, on March 9, 2020.

Members of a Taliban delegation, including their chief negotiator Mullah Abdul Ghani Baradar, leave after peace talks with senior Afghan politicians in Moscow, Russia, on May 30, 2019.

Afghan civil activists gather along a road during International Women’s Day in Kabul, Afghanistan, on March 8, 2020.

Wakil Kohsar/AFP via Getty Images

Men inspect the site of a blast inside a mosque in Kabul, Afghanistan, on June 12, 2020.

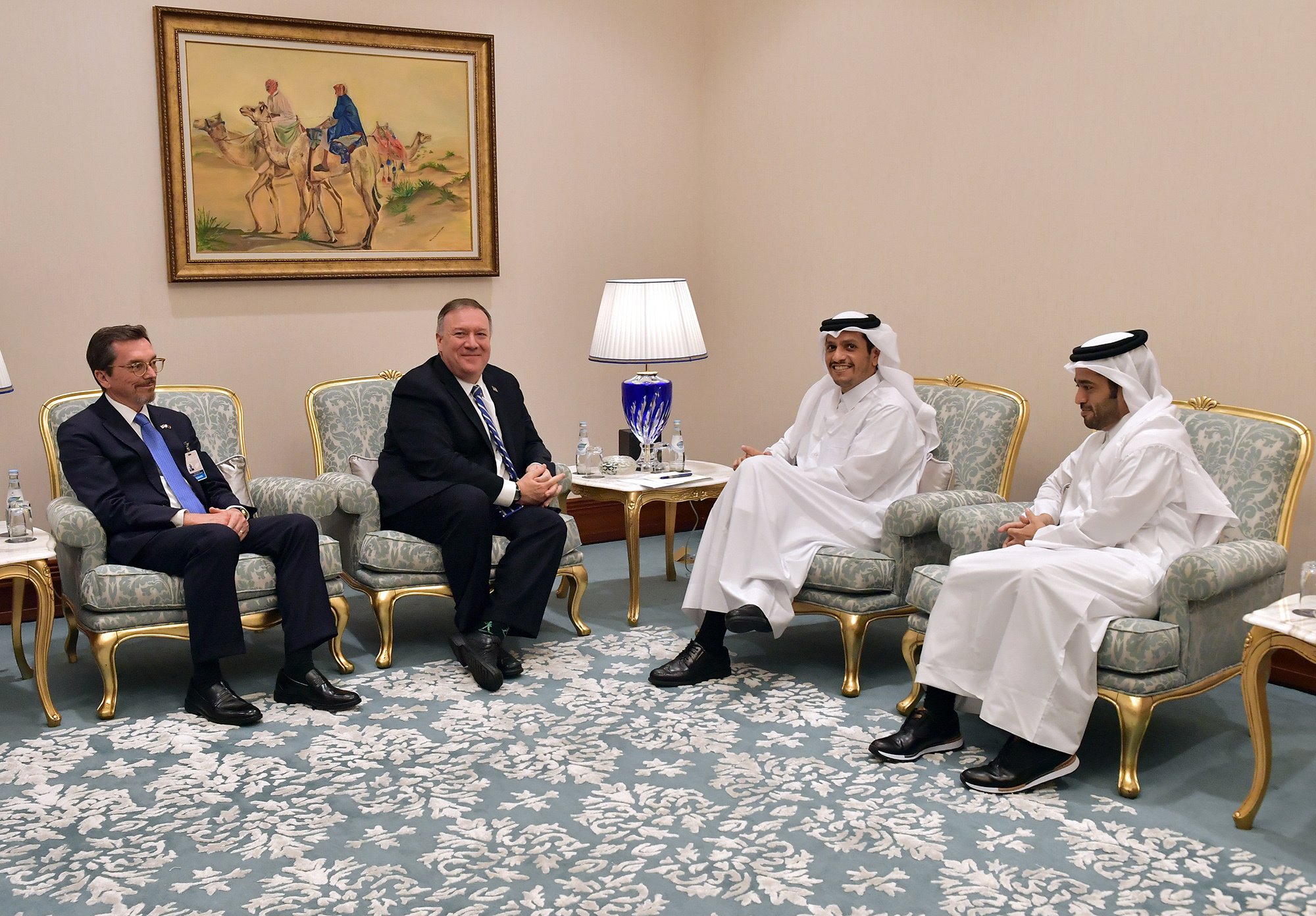

The Qatari Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Foreign Affairs meet with U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo on the sidelines of a signing ceremony between the United States and the Taliban delegation in Doha, Qatar, on February 29, 2020.

Afghan women attend a consultative grand assembly, known as Loya Jirga, in Kabul, Afghanistan, on April 29, 2019.

Freshta Karim, founder of a mobile library bus, checks on schoolkids in Kabul, Afghanistan, on July 2, 2019.

School children take part in a lesson in an open-air classroom in Laghman Province, Afghanistan, on January 20, 2019.

Noorullah Shirzada/AFP/Getty Images

Afghan men take part in prayers at a mosque during Eid al-Fitr in Kabul, Afghanistan, on May 24, 2020.

U.S. President Donald J. Trump speaks to U.S. troops during an unannounced visit to Bagram Air Base on Afghanistan, on November 28, 2019.

An Afghan man prays on a hilltop during the Islamic holy month of Ramadan on the outskirts of Mazar-i-Sharif in Afghanistan, on May 15, 2020.

Farshad Usyan/AFP/Getty Images

A meeting is chaired by former President of Afghanistan Hamid Karzai to mark a century of diplomatic relations between Afghanistan and Russia in Moscow on May 30, 2019.

Sefa Karacan/Anadolu Agency/Getty Images

In the front seat of a mini-bus, Razia Dalili gestures as she drives women passengers in Kabul, Afghanistan, on October 31, 2019.

Wakil Kohsar/AFP/Getty Images

The Secretary-General of NATO Jens Stoltenberg speaks at a press conference with the President of Afghanistan Ashraf Ghani in Kabul, Afghanistan, on February 29, 2020.

Wakil Kohsar/AFP/Getty Images

Afghan Foreign Minister Salahuddin Rabbani, Pakistanii Foreign Minister Shah Mehmood Qureshi, and Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi sign a memorandum of understanding on cooperation in fighting terrorism in Kabul, Afghanistan, on December 15, 2018.

Students attend Shaidayee High School in an internally displaced persons (IDP) camp in Herat Province, Afghanistan, on June 18, 2019.

Kate Geraghty/Fairfax Media/Getty Images

Chinese Ambassador to Afghanistan Wang Yu hands over medical supplies to Second Vice President of Afghanistan Mohammad Sarwar Danish in Kabul, Afghanistan, on April 2, 2020.

Zou Delu/Xinhua/Getty Images

Afghan Taliban fighters and villagers attend a gathering as they celebrate the peace deal signed between the United States and the Taliban in Laghman Province, Afghanistan, on March 2, 2020.

Wali Sabawoon/NurPhoto/Getty Images

Afghan security personnel inspect the site of a car bomb blast near the destroyed office building of Afghanistan ’ s intelligence agency in Aybak, Afghanistan, on July 13, 2020.

Afghan Member of Parliament Shogofa Noorzai poses for a portrait at her office in Kabul, Afghanistan, on March 4, 2020.

Scott Peterson/Getty Images

Afghan school children attend classes at the Ariana Kabul Private School in Kabul, Afghanistan, on September 17, 2019.

Scott Peterson/Getty Images

After nearly two decades of war and several stalled peace talks, the United States, the Afghan government, and others are eager to see renewed efforts to negotiate peace in Afghanistan. Peace is not guaranteed, however, and numerous challenges remain—including implementing the U.S. agreements with the Taliban and Afghan government and kickstarting viable intra-Afghan talks, as well as addressing systemic domestic challenges in Afghanistan.

The United States’ allies and coalition partners, as well as the UN Security Council and regional parties to the conflict have expressed support for the U.S.-Taliban agreement and U.S.-Afghan joint declaration. However, these recent efforts toward peace in Afghanistan will be difficult to enact given the uncertainty around the United States’ timeline for troop withdrawal and removal of sanctions on the Taliban, concerns about the future of counterterrorism operations within the frameworks of these agreements, and the Taliban’s apparent resurgence over the past year.

First, it is uncertain how the United States and allies will be able to assess that necessary conditions have been met for a full drawdown of military forces, and whether the United States will be able to renegotiate, and ultimately remove, sanctions on the Taliban. The first 135 days of the agreement have passed and the United States has reduced troop levels to 8,600 and removed troops from 5 bases, as stipulated by the U.S.-Taliban agreement and the joint declaration with the Afghan government. However, Taliban attacks increased across the country following the signing of the agreement and it remains to be seen whether and how the United States will respond. The United Nations’ Afghanistan sanctions monitoring team has also raised concerns [PDF] about the ability of the United States and UN Security Council to remove sanctions on the Taliban given its connections with al-Qaeda and whether it will be possible to address the Taliban’s reliance on narcotics trafficking for profit.

Second, in order to prevent “armed groups” or “terrorist groups” from using Afghanistan as a base, both the U.S.-Taliban agreement and joint declaration acknowledge that the Taliban and Afghan National Defense and Security Forces (ANDSF) will need to conduct counterterrorism operations. However, neither agreement acknowledges or grapples with whether the Taliban and ANDSF—and coalition forces, as appropriate—will coordinate these operations, how they will validate that attacks have not been carried out or supported by subgroups within the Taliban, nor how the Taliban will prove that it has suppressed Islamic State in Khorasan operations. Moreover, the Taliban’s connections to al-Qaeda, largely through the Haqqani network, could prove difficult to sever. Despite agreeing to sever ties with terrorist groups under the agreement signed with the United States, a UN report [PDF] published in May 2020 found that the Taliban remains in close contact with al-Qaeda.

Finally, despite observing short cease-fires since the agreement was signed, the Taliban seems to have escalated its military campaign against Afghan security forces. In June 2020, the Afghan government reported that attacks by the Taliban were up nearly 40 percent over the previous three months when compared to the same time last year. In July, President Ghani warned that ongoing high levels of violence pose a serious challenge to the beginning of negotiations, and the Afghan government said that more than 3,500 security forces personnel have been killed since February.

The internal cohesion and perceived weaknesses of both the Afghan government and the Taliban will also play a role in the ability for all parties, including the United States, to implement these agreements.

Intra-Afghan negotiations resulting in tangible peace and a credible power-sharing agreement in Afghanistan face real challenges. Issues include the concerns around the prisoner swap; the composition of a future Afghan state and government, and reintegrating the Taliban into the Afghan security forces; and the internal cohesion of the Taliban and Afghan government, and whether the Taliban is actually committed to an intra-Afghan peace process, or is using its participation as a bargaining chip to further its own objectives.

First, concerns around the prisoner swap had to be resolved before prospects for intra-Afghan talks became a reality. The Afghan government had initially balked at releasing prisoners on the Taliban’s list, insisting many of them were too dangerous. In August 2020, however, the Afghan government convened a loya jirga—a grand assembly of elders—to discuss and eventually approve the release of the approximately four hundred remaining Taliban prisoners who had been accused of major crimes. Following a decree from President Ghani, as of September 2020, the Afghan government had released all five thousand of the prisoners from the list requested in exchange for nearly eight hundred and fifty Afghan security forces. The final six Taliban prisoners, accused of playing a role in the deaths of American, Australian, and French nationals, and whose proposed release had prompted international protest, were also released and flown to Qatar to be placed under house arrest, clearing the way for negotiations to formally begin.

Second, questions over the composition of a future Afghan state will need to be resolved for negotiations to be considered a success. The Afghan government and Taliban will need to address fundamental concerns about ideology, as well as broad-ranging and practical concerns about power-sharing, transitional justice, and disarming, demobilizing, and reintegrating the Taliban into the Afghan security forces. The Taliban’s stated goal for Afghanistan has been to re-create the Islamic Emirate that was overthrown in 2001. If the Taliban is serious about participating meaningfully in these negotiations and coming to a power-sharing agreement with the Afghan government, it will have to be flexible and willing to compromise on this goal, as well as others.

Third, the Taliban and Afghan government face internal challenges that threaten their cohesion and credibility. The Afghan government is fragile. It has faced internal divisions over Ghani’s acceptance of the U.S.-Taliban agreement (which the Afghan government did not participate in) and has been caught up in negotiations over the disputed outcome of the September 2019 Afghan presidential elections. Those elections resulted in a months-long dispute over the outcome, which resulted in both Ghani and Abdullah taking the presidential oath of office in March 2020. While the power-sharing agreement reached by Ghani and Abdullah in May 2020 allows Abdullah to lead the High Council for National Reconciliation, as well as name half of the members of the Afghan government’s cabinet, tensions between Ghani and Abdullah, as well as their respective political camps, remain high. Further fractures in their relationship would threaten the ability of the Afghan government to present a unified front in negotiations with the Taliban. Beyond the top-level political tensions, the Afghan government is also plagued by high-levels of corruption and a strained ability to exert control outside of Kabul and a few other major cities. Powerful officials, warlords, and politicians representing Afghanistan’s larger minority ethnic groups may challenge any agreement the government tries to reach with the Taliban.

For the Taliban, internal divisions have complicated implementation of the U.S.-Taliban agreement and raised questions about the Taliban's meaningful participation in intra-Afghan talks. Although Taliban deputy leader Mullah Abdul Ghani Baradar signed the U.S.-Taliban agreement on behalf of the group, the Taliban is not a monolith. It has many different factions that will need to be acknowledged or accommodated in any negotiations. Some members of the Taliban have already refused to acknowledge the agreement and some may be seeking to strengthen ties with the Islamic State in Khorasan. Because some of these factions may not be willing to compromise, the prospect that further splintering within the movement could seriously hinder efforts toward peace.

Finally, after perceiving a signed deal with the United States as a victory, the Taliban could prolong negotiations to appease the United States—biding its time while the U.S. military completes its withdrawal and enabling the group to then ramp up its military campaign and attempt to overthrow the Afghan government. The Taliban’s recent escalation of violence not only raises questions about its ability to control members of the organization, but also about the Taliban’s commitment to the agreements it signs. If the Taliban simply uses participation in negotiations to appease outside actors or pursue alternate objectives, peace could be compromised.

CPA recently published a Contingency Planning Memorandum, “A Failed Afghan Peace Deal,” by Seth G. Jones, Harold Brown Chair and director of the Transnational Threats Project at the Center for Strategic and International Studies. Jones discusses the significant hurdles remaining for an intra-Afghan peace deal, and outlines steps the United States can take to prevent a failed peace deal in Afghanistan.

A number of domestic issues in Afghanistan will play a role in determining the outcome of the Afghan peace negotiations. Addressing and resolving the future roles of women and civil society, as well as establishing and strengthening the rule of law and government, will be crucial for achieving lasting peace. Regional stability—or instability—and the novel coronavirus pandemic could also affect the future of peace in Afghanistan. So, too, will the Afghan government and Taliban’s ability to carry out counterterrorism operations be important for ensuring a secure and stable country.

The extent to which Afghan peace negotiations are able to incorporate women’s rights, including fundamental human rights, will affect the possibilities for peace in Afghanistan. Women face barriers at all levels of Afghan society, and the quota of women serving in official positions is still low.

The U.S.-Taliban agreement and U.S.-Afghan government joint declaration do not contain provisions carving out a space for civil society organizations to participate meaningfully in discussions about the country’s future. This could affect the inclusiveness of the intra-Afghan negotiations and the ability of the negotiations to reflect concerns of the wider population.

Important questions concerning a future Afghan government revolve around its composition, the judiciary (including transitional justice) system, and the rule of law.

The stability of Afghanistan is inherently connected to regional stability and security. Destabilizing trends in bordering countries, and their possible spillover into Afghanistan, would likely threaten progress on a peace process.

While Afghanistan faces domestic challenges related to counterterrorism within its own borders, the transnational nature of terrorism means that several terrorist networks, including al-Qaeda and the Islamic State in Khorasan, are still active in Afghanistan and across the broader Middle East and South Asia. Preventing terrorism from spreading within Afghanistan has been a core objective of the United States, and how to address terrorism has been a large point of discussion in negotiations.

The future of peace in Afghanistan will depend on how major regional powers, including Russia, China, India, Pakistan, and the European Union, act in ways that could undermine the peace process—or propel it forward. Tensions among the major powers—the United States, China, the European Union, India, and Russia—and others are increasing, which could affect the outcome of the Afghan peace process as each power attempts to secure its own interests in the region. Moreover, deteriorating bilateral relationships between two or more regional powers (for example, between the United States and Iran) could also undermine efforts to cooperate, or otherwise sway the outcomes of intra-Afghan negotiations.

The decades-long war in Afghanistan and ensuing regional instability affects each of these regional powers; likewise, regional powers have their own interests in Afghanistan, and may use subversive means to secure them. For example, Iran is known to fund networks of proxy militias throughout the Middle East, and is interested in both countering the United States and supporting groups in Afghanistan that align with broader Iranian objectives. Similarly, Russian foreign policy toward Afghanistan appears to operate on several levels, only some of which are transparent. While the Kremlin invited representatives of the Taliban to peace talks with the Russian government in 2019, recent U.S. intelligence reports have revealed that the Kremlin’s relationship with the Taliban may extend beyond negotiations to undermining U.S. military operations in Afghanistan. China, which shares a border with Afghanistan, is interested in a stable Afghanistan that facilitates the growth of the Belt and Road Initiative and in counterterrorism initiatives that prevent terrorist spillover into China’s western provinces. India, which often views Afghanistan through its relationship with Pakistan, is interested in containing terrorism and checking Pakistan’s power in the region. Pakistan, which shares a long and complex history with Afghanistan, must balance a number of interests and relationships, including with the United States and international financiers, while contending with domestic politics that often oppose the involvement of these powers in Pakistani and Afghan affairs. The EU and NATO are major regional powers that have a stake in seeing a secure, stable Afghanistan, for the collective security of the states that each power represents, and also to scale back commitments in a time of global financial loss.

As intra-Afghan talks provide an opportunity for charting a path forward, these external parties to the conflict will play an outsized role in ensuring that negotiations result in a stable, comprehensive deal that reflects the priorities of all parties to the intra-Afghan talks.

Read more about the role of outside powers in Afghanistan by exploring the CFR Backgrounder, "U.S.-Taliban Peace Deal: What to Know," by Lindsay Maizland.

Explore additional resources on domestic and regional challenges in Afghanistan and the roles of regional powers.

The Council on Foreign Relations acknowledges the Rockefeller Brothers Fund for its generous support of this project.